Fiona Jack, Installation – various media, Projectspace and Spare room, Melbourne, Australia. International Artist in Residence partnership between RMIT School of Art and The South Project inc., August 2008

TAXI, text by Nicola Harvey

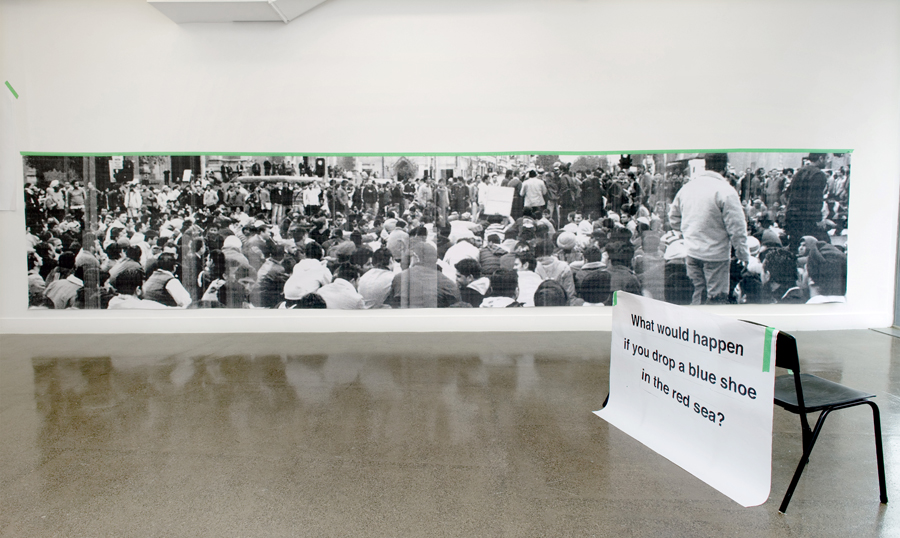

One of the impediments to writing smoothly about a site-specific art work yet to take form is the likelihood of being distracted by the elaborate web of research documents and entertaining facts recounted by the artist, in this instance, over a cup of tea. Fiona Jack’s art is typically shrewd, complex and persistently well researched, thus it seems appropriate to review a few facts, figures and anecdotes relating to the current exhibition at RMIT Project Space, whilst bearing in mind that such information does not fully elucidate the concerns the artist is attempting to translate visually. However, on the 29th April 2008 a young, part-time taxi driver was stabbed, allegedly by his passenger, and left for dead near Queen’s Parade in Melbourne. On the 30th April approximately 300 Melbourne taxi drivers, reportedly mostly of Indian descent, staged a protest at the intersection of Flinders and Swanston Streets calling for immediate action by the Victorian State Government to improve security for taxi drivers and to introduce a system of prepaid fares for all passengers between 10pm – 5am. Oh, and they also requested all parking tickets incurred during the protest be waivered. Something else worth noting is during the period 2006-07 the second highest group of immigrants who became Australian citizens were from India. Rounding out the top 10 countries from which new Australian citizens derived were: UK, China, New Zealand, South Africa, Philippines, Sudan, Malaysia, Afghanistan and Vietnam.1 Also, according to the Melbourne Herald Sun, around 400 Victorian taxi drivers are injured every year on the job.2

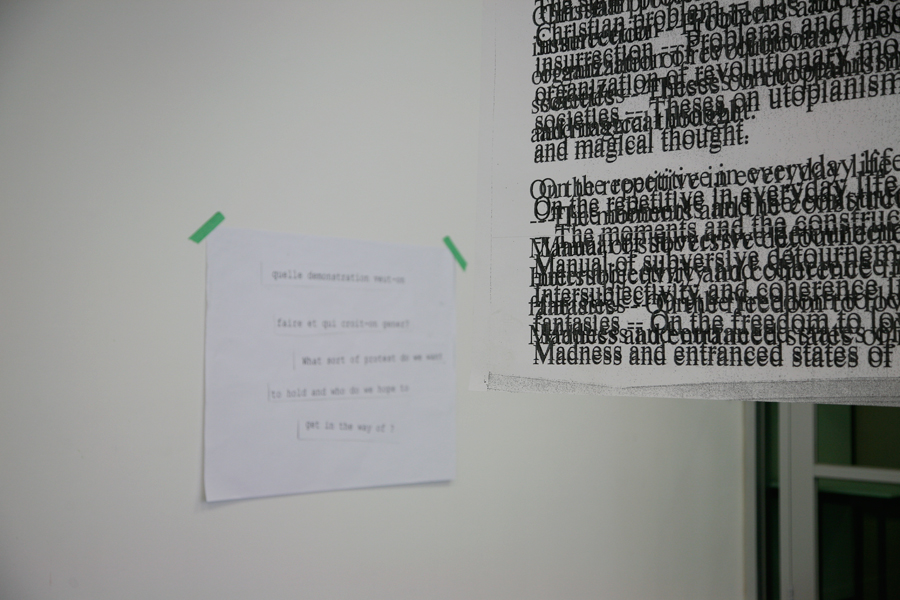

As this essay is not intended to descend into a diatribe on cultural difference let me elaborate that Jack’s interest in such miscellaneous pieces of information are but part of an endeavor to create site-specific projects that are concerned with art historical and institutional narratives, but also with integrating art more directly into the realm of the social in order to redress certain issues. In short, Jack’s interest in the Situationists’ legacy posits her practice as “an art of dialogue, an art of interaction”.3 Without the strategy of interaction (in Melbourne this included interviews, media research, and days hanging with the cabbies at the Tullamarine airport ramp), her site-specific projects would be almost reticent (albeit sublime in their abstract, painterly expanse). In her research Jack seeks out moments that can be defined as a tipping point in a community – an event that creates an indelible, unretractable mark on the social fabric. For recent exhibitions, Jack has delved into the history and legacy of the 68 Watts riots in LA (using Guy Debord’s seminal text, ‘The Decline and Fall of the Spectacle-Commodity Economy’ as a catalyst), and explored the tradition of muraling and graffiti in Santiago, Chile. Which, as Jack discovered during a residency in October 2006, is still propagated by the Brigada Ramona Parra, a mural brigade established by the Youth League of the Communist Party during the Pinochet dictatorship, who continue to present a dissenting political voice in Santiago as they did during the regime. In both instances Jack spent many weeks infiltrating the daily routines of the communities marked by these events and traditions. In Santiago Jack’s interaction with the politically motivated mural brigade, plus reconnaissance on various parts of the city (predetermined by the dropping of nine corn kernels on a map of the city by an old woman at one of the Fondas taking place around Santiago during the celebration of Chile’s national day), and daily conversations with locals who lived near the wall Jack had commandeered as her site – a 36 metre wall encircling the art gallery Centro Cultural Matucana 100 – inspired an expansive abstract mural running the length of the wall. It commanded the attention of passers-by with its shear visual audacity, but did not impinge on their journey with confronting didactics. It was not until a passer-by stopped to consider the work would they be delighted by the tiny phrases and fragments of text scattered across the surface like a dandelion head blown into the wind. These words were totems for the true ‘site(s)’ of the work, not a location on a map but a series of situations laid out like an itinerary.

Such regular movement between countries and moments and amongst people, whilst informing Jack’s practice, does not exist without its own set of problems. The very nature of artist residencies and site-specific projects (that being transitory) have the potential to highlight cultural difference as a principal discursive fiction. It is difficult to avoid producing a work that Miwon Kwon so aptly suggests can be a “temporary antidote for the anxiety of boredom”4. Thankfully Fiona Jack has not yet appeared bored and continues to navigate her itinerary of sites with a clear view of preserving fragments from her interactions to be translated onto the gallery wall (or a specific spatial site), without pivoting the spotlight directly onto her sources. Jack’s practice resists producing a spectacle, instead she seems focused on marrying a commanding painting talent with the intricate details of her research; the result being far more exciting than the pile of newspaper clippings I have in front of me now.

Nicola Harvey is a writer and Communications and Distribution Assistant for frieze Magazine.

Footnotes:

1. Australian Department of Immigration and Citizenship. www.immi.gov.au/media/statistics/.

2. Gareth Trickey, ‘Cabbies in Safety Victory’, Herald Sun, April 30th 2008

3. ‘Situationist Manifesto’, 17 May 1960, Situationist International Online, www.eddc.vt.edu

4. ‘One Place After Another: Notes of Site Specificity’, Miwon Kwon, 1997. in Theory in Contemporary Art since 1985, ed. Kocur & Leung, (Blackwell: Australia) 2005, pg 49.